The activation or deactivation of genes can occur due to adverse experiences in life, and these configurations can be passed from parents to children

Understanding child development from conception, discovering the impact of infections and other injuries during pregnancy, and seeking to optimize the quality of child hospital care are some of the main lines of research in pediatrics at the D’Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR). However, to understand that the field only investigates the health and well-being of babies and newborns is a misconception.

There is a new scientific scenario understanding that, at the time when our organism is developing – as in the embryonic, fetal, and postnatal periods –, the occurrence of certain adverse factors can increase our susceptibility to chronic diseases in adulthood, such as diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular problems, and even mental disorders. This strand of study is called DOHaD (developmental origins of health and disease), and one of the most investigated topics within the field is epigenetics, the science that researches how the environment in which we live interacts with our gene expression, that is, in the activation or silencing of certain genes.

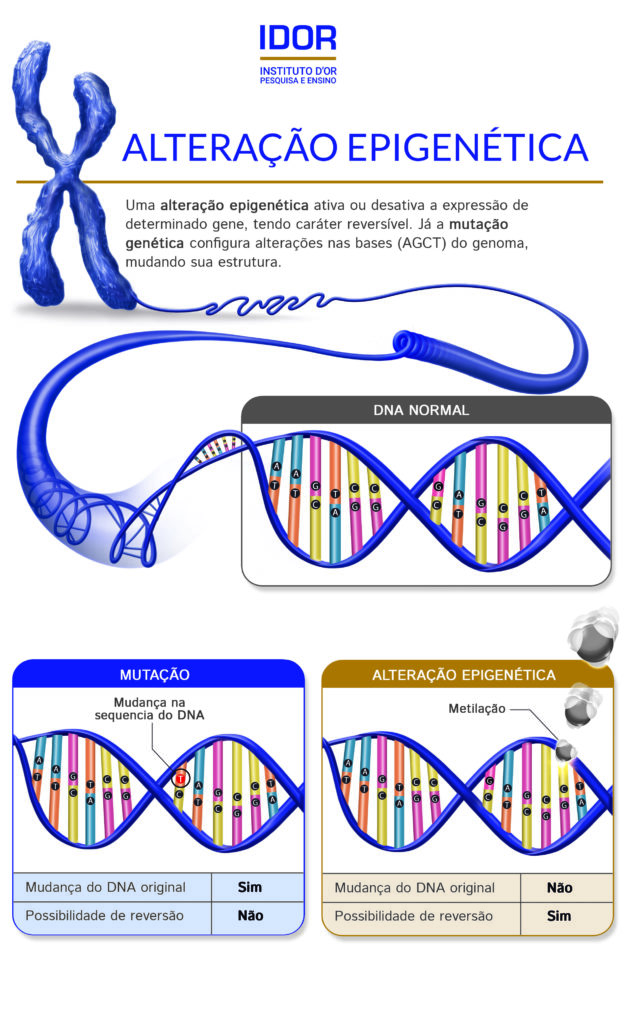

“When we talk about genetic alteration, it necessarily implies a mutation, a change in the sequence of the bases that make up the DNA. Epigenetics is not that”, begins Dr. Arnaldo Prata, pediatrician, professor, researcher, and coordinator of pediatrics at IDOR. “If all the cells in our body have all genes, our complete DNA, how do they turn into specific cells, be it a cardiomyocyte in the heart, or a neuron? To do so, the countless genes that are uninteresting for the function of a specific cell are deactivated, and only the general genes of the cell and those related to that specificity work. This activation and deactivation is a process that does not cause DNA mutation, but is still capable of causing relevant impacts, which can even be transmitted from parents to children. This is epigenetics.”, he explains.

Epigenetics emerged as a concept in the 1940s, but because it is still an incipient theory, it has only in recent years gained greater interest from scientists. The process of DNA methylation, a chemical modification that occurs in gene promoter regions and plays a significant role in activating and silencing gene expression, is one of the main focuses of research in the area.

Quickly recapitulating the concepts of genetics, our DNA is composed of two paired strands, composed of four nitrogenous bases that are chained sequentially through specific connections between them: Adenine (A) binds to Thymine (T) and Guanine (G) binds to Cytosine (C). Methylation is a process that occurs in the Cytosine-Guanine sequence, through the addition of a methyl radical to Cytosine. This process is very common in the so-called promoter regions, areas capable of making the gene active or inactive for certain transcription factors. “In this promoter region, if a methyl radical connects to cytosine, it becomes methylated and this modification affects the functioning of transcription factors, and that cell will no longer produce a certain protein, for example. Several diseases and aspects of health itself are regulated by these epigenetic mechanisms. We are a great algorithm”, illustrates the researcher.