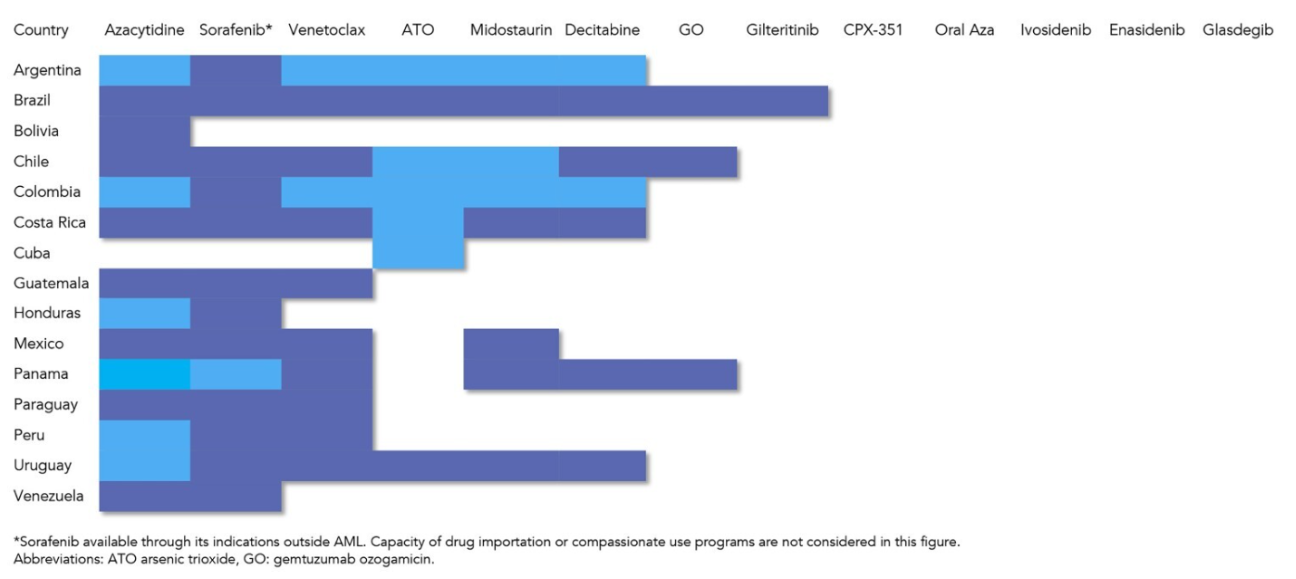

The availability of therapies for acute myeloid leukemia also varies between high- and low-income countries, showing heterogeneity even among Latin American countries. In one of the primary treatments for AML, intensive induction chemotherapy, whose main objective is to eliminate a large portion of cancerous blasts, the early mortality rate varies between 3% and 6%, according to recent clinical trials. However, when implemented in low- and middle-income countries, these rates increase, and in Brazil, it reaches 41% among older adults.

The authors believe that this disparity could be reduced through urgent treatment measures for patients with highly elevated white blood cell counts, as they have the highest mortality rate during induction treatment. Another issue is the patient’s profile, as many already have comorbidities that worsen the disease. Additionally, treatment delays due to waiting for genomic results and shortages of chemotherapy due to mismanagement of government resources are also constant obstacles faced in Latin American countries.

“One interesting aspect of this study is that we compared aspects of acute myeloid leukemia not only between Latin America and developed countries but also among Latin American countries themselves. It’s a highly heterogeneous scenario, even within Brazil. In the country, we have a greater concentration of resources in the Southeast region, which also reflects in the availability of AML therapies,” the researcher notes.

In addition to chemotherapy, another essential treatment for severe cases of AML is bone marrow transplantation, now referred to as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In this technique, the disease is treated more aggressively with known marrow-toxic drugs, and recovery occurs from the patient’s young cells or from donor cells. When a patient’s cells are used, it is called autologous transplantation, and when cells come from a donor, it is called allogeneic.

In Latin America, a significant facilitator of allogeneic transplants has been the haploidentical donation. In this method, only 50% compatibility is needed for the transplant, which is usually done by a first-degree relative of the patient. This medical advance avoids waiting for a more compatible volunteer, a challenge that is difficult to overcome when most Latin American countries lack unrelated donor registries, with Brazil being an exception through the Brazilian Registry of Volunteer Bone Marrow Donors (REDOME).

In the absence of donors, the study also considers that autologous transplantation should be an effective and economical option in Latin America, as it reduces the chance of adverse effects such as the need for blood transfusion and hospitalizations. The article mentions that this strategy was studied in previous research, where autologous transplants were performed in patients after chemotherapy treatment. The overall survival of participants at 2 years ranged from 74% to 79%, with a disease-free survival of 61%.

Based on the specifics of AML diagnosis and treatment in Latin America, the review’s authors emphasize that scientific collaborations led by Latin American researchers are paramount to better adapt the implementation of therapies to the needs of these countries. They also stress the importance of investing in clinical education and accessible therapies, not only in Latin America but in other low- and middle-income countries facing similar challenges and disparities related to the disease.